LLMs for Wi-Fi Support - Part 2: What Changes When the AI Assistant Has Access to More Wi-Fi Data?

Sifting Signals: commentary on using data to reason about Wi-Fi behavior and use cases at scale, whether you are designing features, tuning performance, or debugging issues.

Summary

In the previous article, we looked at a familiar user complaint - ‘Connection ‘feels’ very fast in the living room where the router is located but in the office, the video calls and browsing ‘feel’ slow’ - and examined how an off-the-shelf large language model (LLM) behaved when given the client-side logs (RSSI, noise, SNR, Tx PHY rate, channel, RTT, location). The AI assistant could identify broad Wi-Fi changes between the two locations (drop in signal strength, lower PHY rates) but introduced “interference” as a likely cause without any notion of how busy the wireless medium was. If you haven’t already read the previous article, you can find it here: Part 1

This article adds ‘channel utilization’ as a way to estimate how busy the wireless medium looks during the user’s session. Using the same two room setup and data as before, we compare three cases:

- No channel utilization input

- Quiet channel

- Busier channel

These examples use illustrative utilization values (15% as “low” and “45%” as “busier”) from the AP’s point of view rather than measured numbers. We then look at how the AI assistant’s responses change in each case and qualitatively assess whether the causes and next steps stay grounded in the available evidence, and where they still fall short.

The main takeaway is that giving the assistant ‘utilization’ information helps it reason about the causes of the complaint more concretely. At the same time, when utilization looks similar in both rooms, it tends to de-prioritize interference. In real networks, weak coverage can hurt more when the channel is busy than when it is quiet. An AI-enabled Wi-Fi system should consider utilization and coverage as interdependent factors to arrive at a reasonable explanation.

1. Recap: User Complaint and Setup

Using a simple example, the previous article looked at the assistant’s behavior to extract meaningful lessons.

- User complaint: Connection ‘feels’ very fast in the living room where the router is located but in the office, the video calls and browsing ‘feel’ slow.

- Setup: The router is located in the living room while the office room is farther away.

- Per-second client-side logs: RSSI, noise, SNR, Tx PHY rate, channel, LAN/WAN RTT, location.

In the previous article, we saw that the LLM correctly identified broad patterns such as the office had weaker signal and lower Tx PHY rate but still came up with “interference” as one of the likely causes without any data about interfering sources or the extent of interference. In this part, we provide the assistant with an additional piece of information about the ‘busyness’ of the wireless medium.

2. Interpreting ‘interference’

In this article, we use ‘interference’ to mean ‘medium busyness’ that reduces available airtime due to activity on the channel (Wi-Fi contention and/or non-Wi-Fi energy).

Typically, a Wi-Fi system can estimate this ‘medium busyness’ per radio/interface using:

Clear Channel Assessment (CCA) counters on the Wi-Fi chipset:

Chipset vendors often expose internal counters that track how long the Clear Channel Assessment indicates the medium as busy over a time window. From these, a device (AP or client) can derive the fraction of time the medium was busy. Depending on implementation, these counters may include the time spent by the device’s own traffic as well as other energy (Wi-Fi or non-Wi-Fi) on the channel.

BSS Load indicator:

Some access points advertise the channel utilization they observe in beacons and probe response frames using the BSS Load information element (IE). It provides an insight into the AP’s view of channel busy time.

In a real system, ‘channel utilization’ can come from an AP or a client using their respective counters. Each device presents its perspective of medium busyness, based on where it is located and its own hardware implementation. Understanding which implementation your system uses, whether it separates one’s own airtime from other busy time, and whether the value makes sense is important if you plan to feed it as input to an AI assistant.

In this article, we do not focus on the specifics of each implementation. Instead, for simplicity, we use utilization as a coarse indicator of medium busyness during the user’s video call/browsing session.

3. System View: Adding a ‘busyness’ input

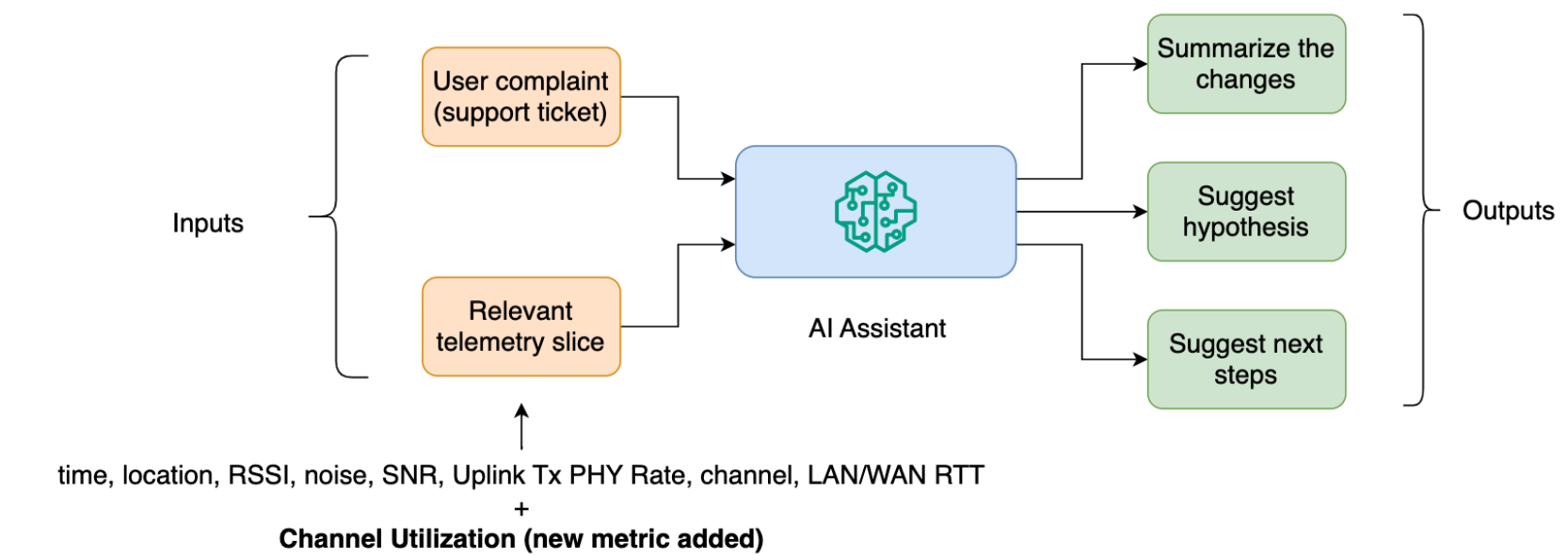

At a high level, the system still follows the conceptual workflow from the previous article where the AI assistant is given the ‘user complaint’ and the relevant telemetry slice consisting of time, location, RSSI, noise, SNR, uplink Tx PHY rate, channel, LAN/WAN RTT. Here, the only change is the addition of a ‘channel utilization’ field as input, which reflects how busy the channel looked during the session.

In the examples that follow, we look at hypothetical utilization values (15% and 45%) that represent lower and higher levels of medium busyness.

4. AI assistant setup changes

We keep the same two room setup, telemetry and model (“gpt-4.1-mini”). The physical setup still consists of a single AP in the living room. The channel utilization is represented as a single value shared by both locations (living room and office) over the entire user session, rather than a per room measurement. The assistant still has to describe changes between the two rooms, suggest likely Wi-Fi causes and propose safe next steps for a home user.

The assistant behavior is illustrated with two changes:

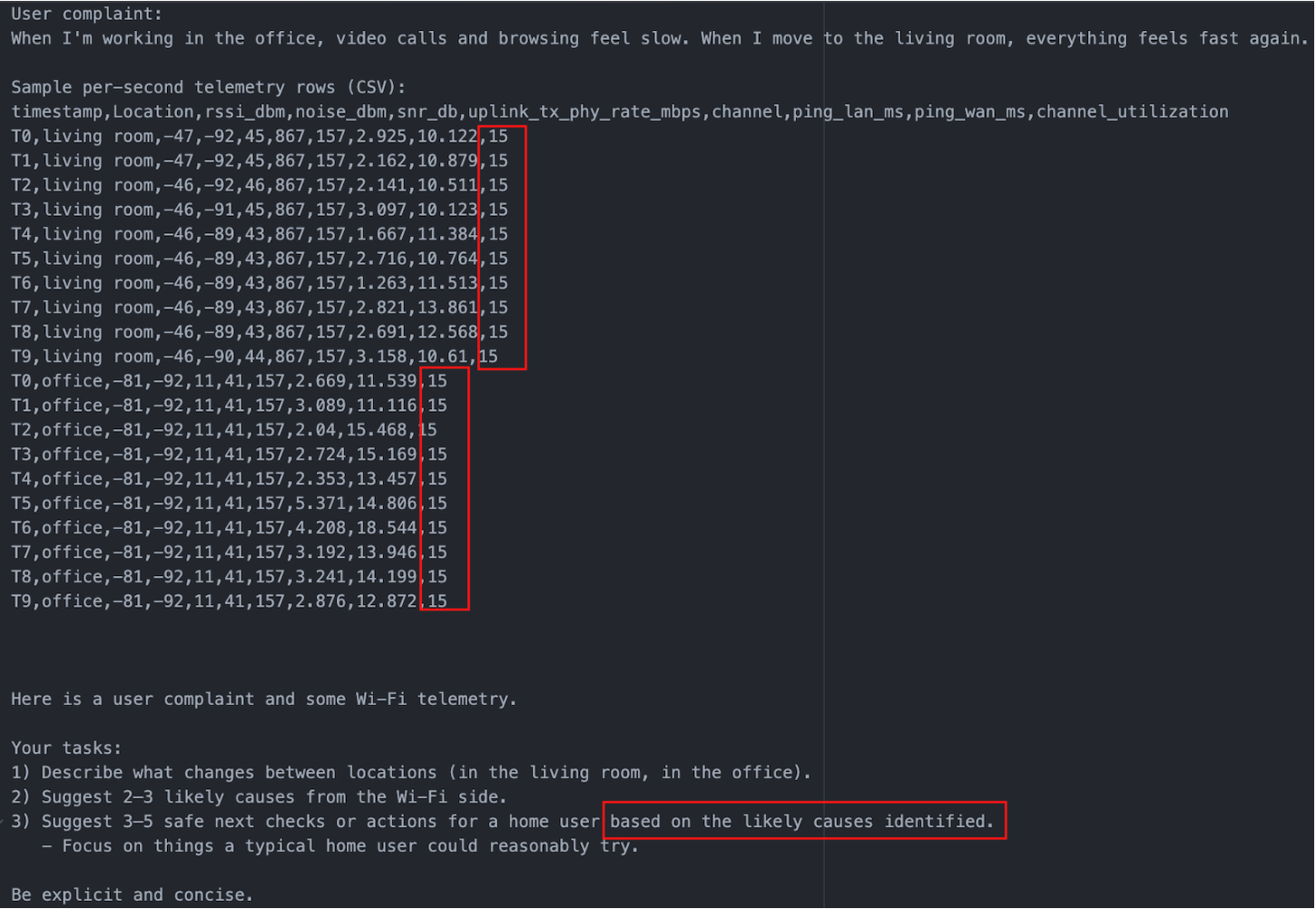

Prompt tweak:

A small guardrail is added to the prompt so that the suggested next steps are tied to its own reasoning. Specifically, the line now reads as “Suggest 3-5 safe next checks or actions for a home user based on the likely causes identified.”

Utilization column variants:

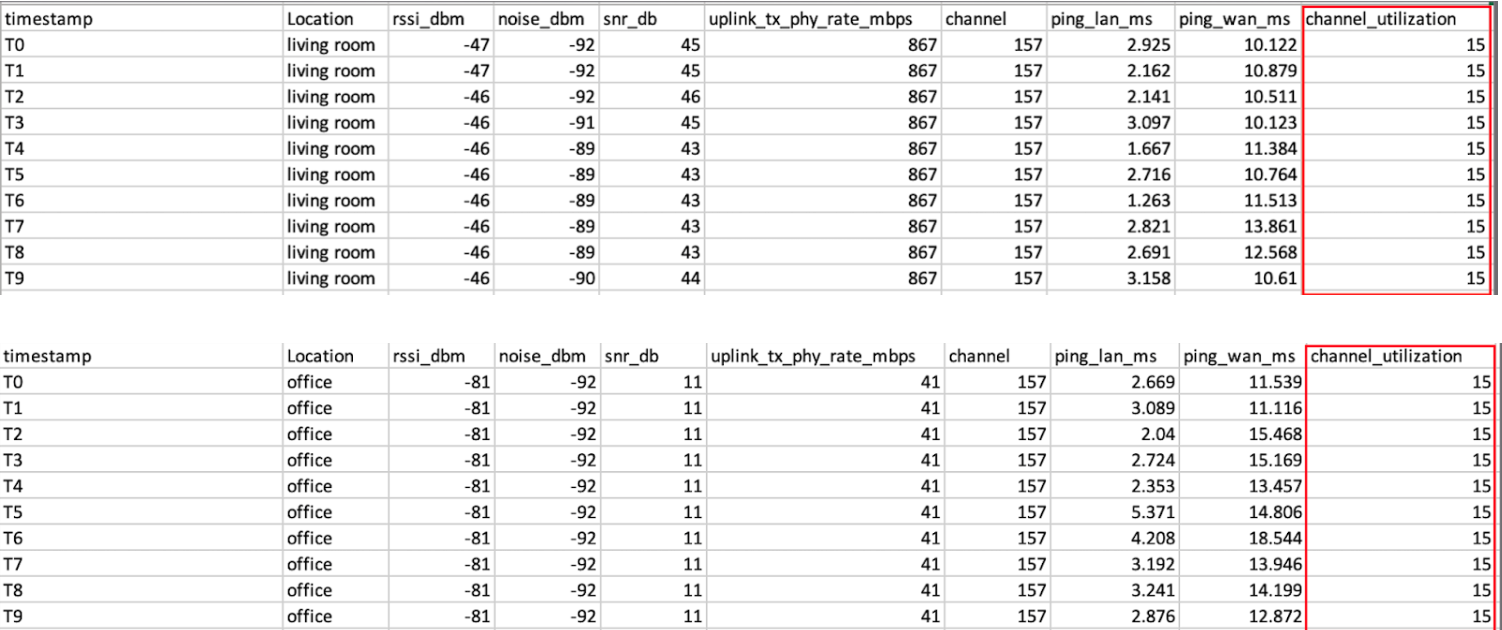

The per-second telemetry table is extended by adding a ‘channel utilization’ column. Three input variants are constructed from the same logs using hypothetical but plausible utilization values:

- No utilization metric

- The table is exactly as in the previous article. No ‘channel utilization’ column

- Quiet channel (15%)

- The table now has a ‘channel utilization’ column set to 15% for every row in both the living room and the office (snapshot below).

- Busier channel (45%)

- The ‘channel utilization’ column is set to 45% for every row (also, same for both locations).

The example snapshot below shows the additional channel utilization column for the ‘quiet’ channel scenario and the prompt tweak as an input to the LLM.

5. Results: how the assistant reacts to utilization

The three input variants change the assistant’s behavior as shown below:

5.1 No channel utilization column:

- As in Part 1, the assistant correctly identifies that RSSI/SNR/Uplink Tx PHY rates are much worse in the office than in the living room. However, it lists ‘interference’ as a likely cause without supporting evidence.

- In this example, it still provides channel change recommendations based on an unsupported ‘interference’ cause, despite adding the prompt guardrail (‘suggest next steps based on the likely causes identified’).

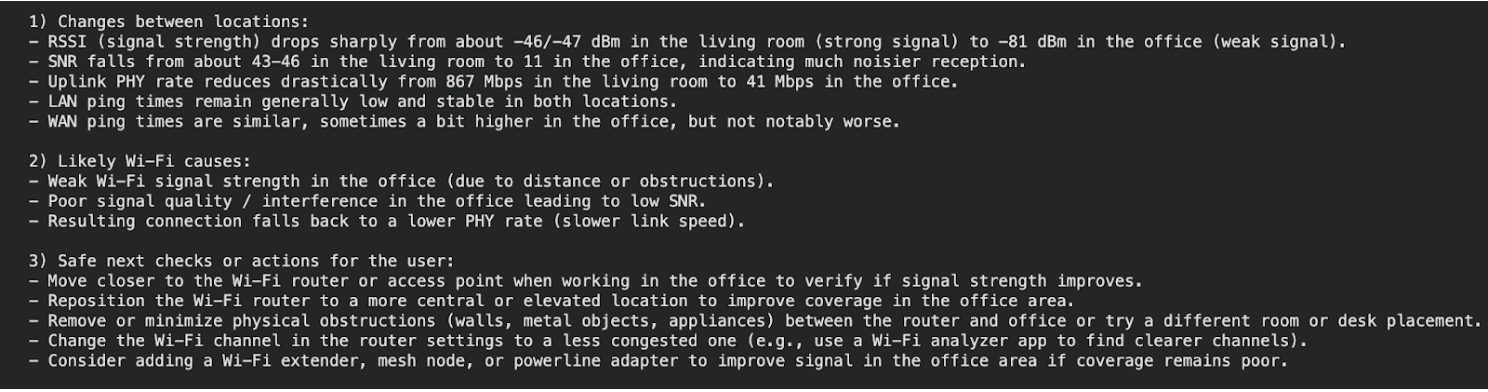

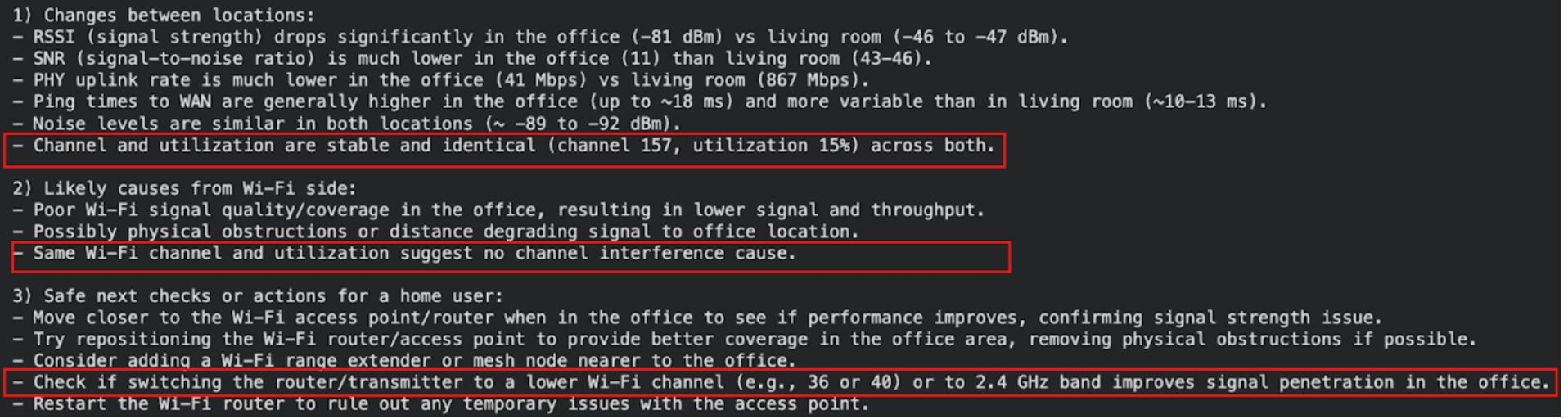

5.2 Channel utilization is low (15%) and set to the same value for both locations

- As in the previous case, the assistant still identifies coverage issues (weak signal, low SNR, low PHY rate) as the main difference between rooms.

- With the new metric, it explicitly notes that channel and utilization values are the same for both locations and uses that to say channel interference is not a likely cause.

- Coverage driven actions (moving closer to the router, repositioning the router, reducing physical obstructions, adding an extender) stay, but now the assistant also focuses on improving range (e.g. switching to a lower 5 GHz channel or the 2.4 GHz band) rather than reducing interference.

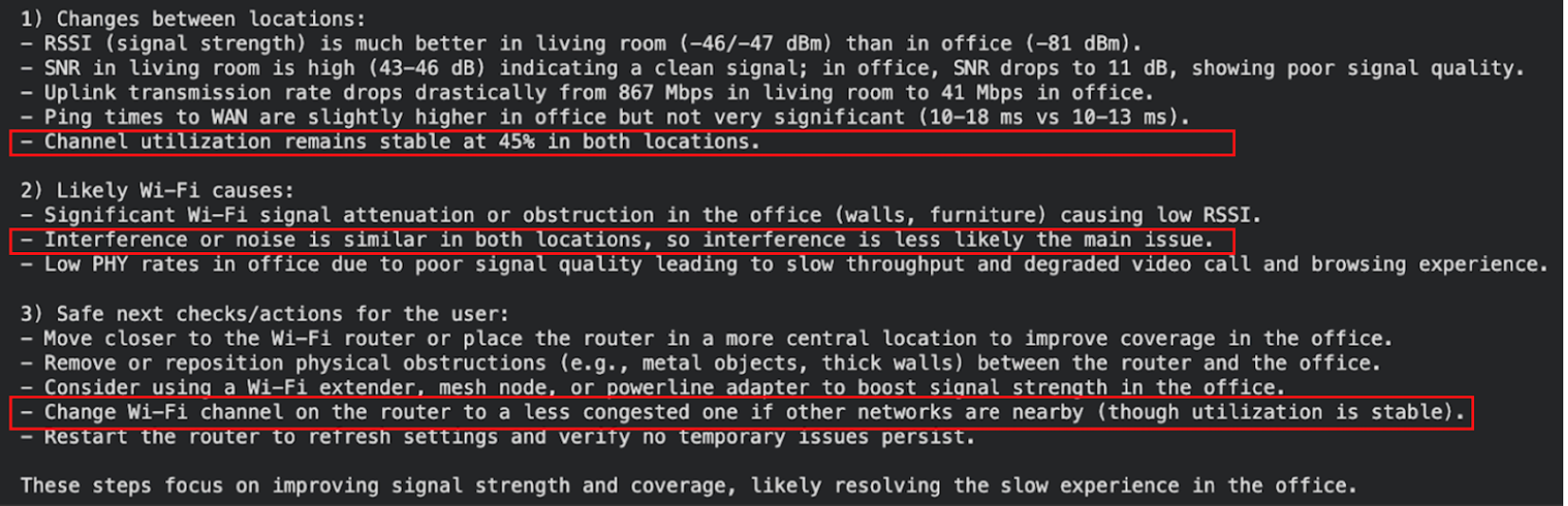

5.3 Channel utilization is higher (45%) and set to the same value for both locations

- Weaker coverage in the office is highlighted again as a primary issue.

- Even though the channel utilization is higher (45%) in this case, the model uses the same utilization value for both locations to say ‘interference’ is ‘less likely the main issue’ behind why video calls and browsing feel slower in the office than in the living room.

- Recommendations are similar to the previous case but with higher utilization the assistant also suggests changing to a less congested channel as a secondary mitigation.

6. Analysis: what a simple prompt change and utilization metric accomplished

In our basic AI system, the prompt tweak (“suggest next steps based on the likely causes identified”) encourages the assistant to suggest actions related to stated causes but it cannot repair a hypothesis that was never based on evidence to begin with.

What the utilization metric changes:

- when utilization is low, the assistant prioritizes coverage as a cause for why the office feels ‘slow’

- when utilization is higher, the assistant still highlights coverage as the main problem, with channel change appearing as a secondary next step

- different utilization levels steer which next steps are suggested (eg., whether to bring up channel change at all)

Some suggestions (eg., switching to a lower 5 GHz channel or the 2.4 GHz band) require engineering judgement before recommending. Lower 5 GHz typically offers minimal range benefit over a high 5 GHz channel, and 2.4 GHz range gains often come with tradeoffs (narrower channel widths, more congestion/interference).

Finally, even though we have managed to improve our AI system, it still fails to capture the nuance that the performance can be degraded by multiple factors operating jointly. In a Wi-Fi system, coverage issues can be worsened by congestion. For example, a weak link falls back to lower PHY rates, spends more time on air (see appendix), and therefore suffers more from contention when the channel is busy. A single utilization value applied to both rooms does not make interference harmless. A production system design should accommodate these interdependent factors to be useful in the field.

7. Conclusion

The two room coverage complaint, revisited with a channel utilization metric, surfaced a few general lessons for building an AI-enabled Wi-Fi system:

- prompt changes without the right metrics cannot make up for missing, incomplete, or inaccurate evidence

- additional metrics (like channel utilization) can help constrain when the assistant brings up a cause (like interference or congestion), instead of using it as a generic explanation

- a reliable system requires understanding how different Wi-Fi factors interact, for example, weak signal and congestion can degrade performance together

- some suggestions still require engineering judgement before recommending to the end user (for example, switching to a lower 5 GHz channel or the 2.4 GHz band)

If you’d like to discuss how to choose and validate the right metrics, and design AI-enabled Wi-Fi systems that use them reliably, feel free to reach out.

8. Appendix

In order to get insight into how airtime increases at lower rates, let’s consider a simple example and calculate the time on air for a 1500 byte packet.

- In the living room, the link supports a PHY rate of 867 Mbps. A 1500 byte packet would then require:

- In the office room, the link supports a PHY rate of 41 Mbps. A 1500 byte packet would then require:

In reality, the time required for the successful delivery of a packet is higher than that required for just the payload due to protocol overheads (PHY/MAC headers), contention/backoffs, acknowledgements, and retransmissions. However, this simple example helps illustrate the fact that, in our setup, the data transmission for the same application payload takes more than 20x longer at the office link rate than in the living room.